Lessons Learned Working with AI (pt 1)

Prelude

Initially, this blog started as a recap of what I had learned and seen over the past year...

As I continued writing this, it became longer to the point where I deemed it better to be a standalone blog post.

Note that this is after working roughly 6 months as an AI engineer. Hopefully, I will be using this blog as a vehicle to document my learnings and also things that I find.

All text is written by a human. Images are generated with Google Gemini.

A Full Swing to AI

One of the biggest things to happen was my transition from a traditional SWE-based role to an "AI Engineer".

Now that term is quite admittedly loaded. I wasn't even sure of the roles of an AI Engineer.

As I've found out, it comes with a lot!

As the AI pendulum swings back and forth and debates and news cycles debate whether the bubble has burst or not, my own experience gives me a different perspective. Having worked with the technology in a more official setup, I've found some interesting lessons that I've learned:

Build Systems, Clear Hubris

One of the biggest things I've encountered is the amount of hubris that gets generated.

It really blows my mind away. There is just. so. much. code. that can be produced now.

Lines and lines of whatever you want spilling out of a terminal. You can set up demo applications, documentation, hell, even full applications with enough prompting.

I am here to tell you that each line produced is not useful.

A big issue that I have faced, and others face, is dealing with the hubris that gets generated. If left unattended and left as an "clean it up later" item, this innocent-looking hubris can actually be very detrimental.

Simply put, our own context windows and ability are not adept at dealing with millions and millions of lines of code that an LLM can generate. This has other implications that I will address separately, but speaking from a point of working with the systems, you have to stop the hubris.

There are multiple disadvantages of persisting AI hubris in your code spaces

Cognitive Load and Review Fatigue

▶

-

Cleaning up after AI code has been known for some time now. That load works in two ways, and it's a chicken-and-egg situation:

-

Understanding: This is by far the biggest load that I have experienced. Reading someone else's AI hubris code that was "quickly" drafted up is never fun. You can argue that well, don't you have to invest time in reading code anyway? That is true, however, it differs in one unique way:

-

Volume: Since you can use AI to generate "draft" versions of codes and a "simple setup", we end up generating tons of content that we don't really check! That comes to bite us back. The longer you generate and the more you autocomplete, the less understanding you have. In that case, when it lands on someone else's corner, it ends up loaded.

-

-

Now, imagine you are working on a feature. You just churn documents, multiple files with those tell-tale emojis. Over time, you generate something I call review-fatigue.

-

Review Fatigue: You accrue this fatigue when you have to decipher through hubris. This exists for anything sort of hubris (documentation, etc), but as is with AI, these trends are only amplified. Review fatigue can creep up in any place, but with AI, it is much more pervasive and, as a result, much more detrimental. Here's an example below:

-

Since you're working on a tight deadline and it worked, you offload the files you generated to someone else. This actually accrues compound interest. Now, the other person has the following experience:

1: They must either make a decision to discard these files

2: Or, leave them be and understand what they are doing

3: Now imagine making this decision over let's say 3-4 files, each of which are 200 long (and this is taking a much stricter limit. In reality files can be way longer!)

4: = 3*300 = 900 lines; that's almost 1,000 lines of code where you have to decide because the other person didn't.

5: So what do you do now? You do what you can and pass it off. Then you add your own work.

6: So the 3rd person inherits, let's say 1,500 lines: 600 from the 1st person and 900 from you.

7: Scale this to a team, working on a product with fast iterations, and you can see where this goes. At some point, the codebase ends up actually forming AROUND THE HUBRIS. That's not good design, is it?

-

Solution

The solution is to be intentional and build systems at a personal level.

Here are some easy steps that I follow. My goal with these is not to add work for the developer but rather to remove that cognitive load by baking these into the system of how I code. Hence, I say build systems, not hubris.

▶

-

Autodocs: One thing that I love to do is whenever I am done with a unit of work, I like to use my coding assistant to create a .md file that explains all the functions and form of the file. I can then house these in a folder corresponding to the file's name

-

These come in more helpful than you think. This is actually a good instance where the amplification of AI can be exponentially good.

Write what you need to, generate what you need to, and at the end of the day: generate a simple readme about what you just did. -

It seems simple, and that's the point. KISS.

-

-

Be Skeptical: When reviewing code and PRs, put on your pessimist googles. Question the purpose of files and structures.

-

Why are we using a Class here? Do we need an enum type here?

-

Coming from this perspective has helped me to find code that wasn't needed or superfluous code that made writing and understanding difficult.

-

You can ask the AI to do this, but you have to be careful. As we know, sycophancy is a noted concept with LLMs.

-

Sycophancy in LLMs refers to when an LLM is overly flattering or agreeable.

-

Go beyond the demo

If there's something that has flooded tech space since AI has come onto the scene, it is this:

-

You see an amazing demo. Demo offers an amazing ability. Demo is developed with AI. You = happy.

-

The actual product is nowhere near the demo. The full product has risks associated with it. You = sad.

Go on LinkedIn and X, and you will have seen this pretty much everywhere. Demo after demo, short-scale projects that look good on paper. Peel back one more layer, and these demo projects often do not scale to actual products.

This is not a knock on demos, btw. Demos are a really insightful tool. It can allow you to gauge interest and ability.

What's been lacking is going the next step from demo to reality.

Take Builder.ai for example. The startup promised an AI assistant that was said to be a no-code tool. The startup got $700 million in investment from Microsoft and SoftBank.

It got revealed that the AI assistant was just human developers

Ok, you say. That's a startup, but what does that have to do with me?

A similar phenomenon can occur in an enterprise setting, albeit at a smaller scale.

Imagine you come up with an idea, you implement a small demo with small data pieces, maybe some medium complex tasks, and you show it. You get the glitter! Whoo-hoo!

The issue is that this is where most AI projects encounter their biggest problem (and maybe this is an indication of something?).

As you scale up, handling context across a large interface becomes an issues, the correctness of your answers becomes harder to decipher, and yielding results to a customer with confidence becomes a Sisyphus-type of task.

I have had to admittedly face this harsh reality - as someone who gets excited over demos! It has been a mindset shift to move myself away from claiming success at demos.

Make your demos, but realize that this is now the starting bar.

When bringing new features, demos can seem tantalizingly simple to productionize. That's the keyword: tantalizingly.

Remember our earlier motto of build systems, clear hubris. Don't jump into the deep end with a cool-looking demo. Assess the real-time and effort cost to make it actually usable. This is even more important for non-senior engineers (aka me!).

Depth, then breadth

One thing that I've struggled with the most is the pure volume of new things that this field has.

You blink, and there's a new research paper, a new standard, a new format. New is the word of this field. Always something new.

How the hell is someone supposed to swim through this? Let alone find insights and bring them to their project?

And no - summarizing stuff means nothing. Go ahead and summarize the 500 papers. The new frameworks. You will still lose your mind - maybe a tiny bit less, that's all.

The key question, with or without summarization, is finding what's relevant. This is the key idea.

Trying to just summarize everything is like trying to swim in a big ocean. You don't know where to go, where to start. You need a heuristic - something to guide you.

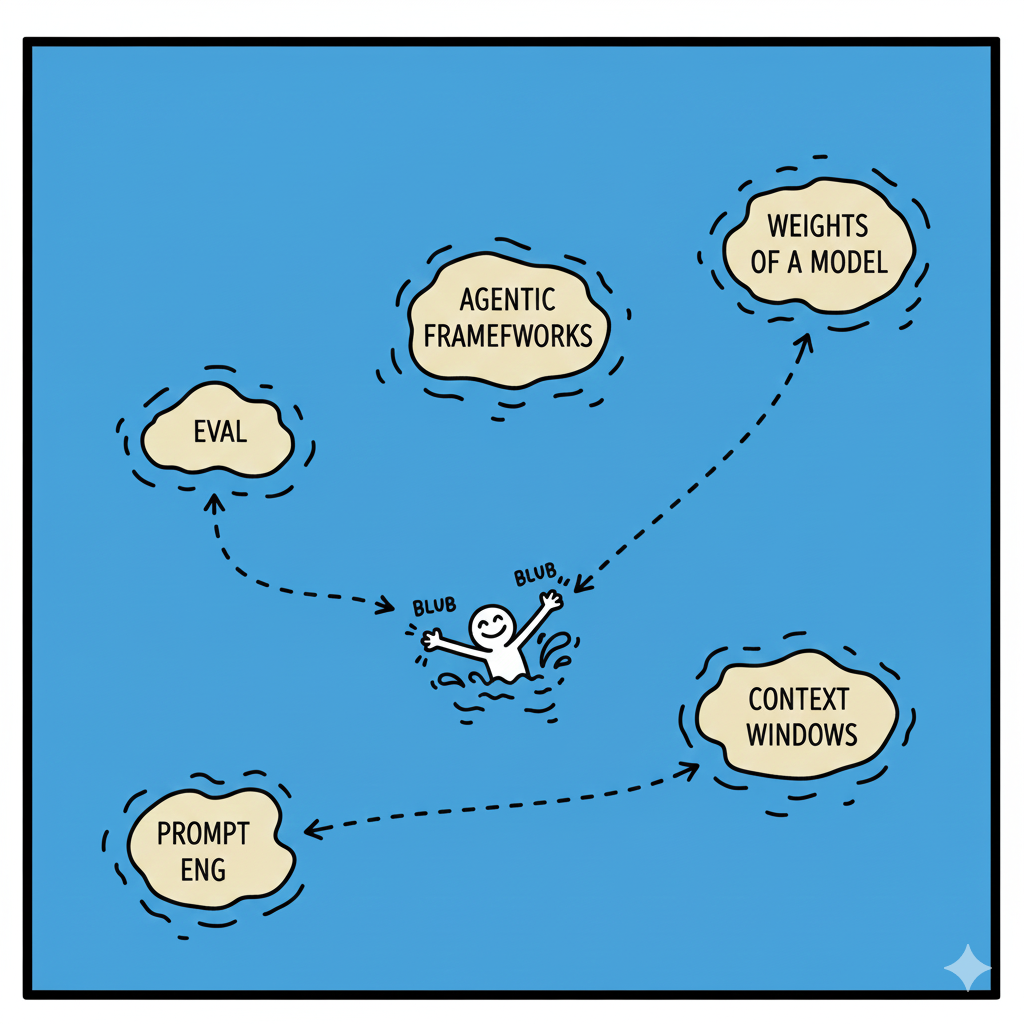

If you're just starting out or are busy with other things like work, life, and your own health, it's better to go narrow and then expand.

By going narrow, you do things:

- You are now swimming a river. Much more manageable and, more importantly, you can actually see a succession of topics - what you will do once you finish one subject.

- You can actually become an expert.

- This is really important. Becoming an expert means you intuitively understand what you're doing. You can transfer this expertise in your own projects.

But notice, I also said "then breadth."

You can definitely go super narrow, but the demands of an engineer will ask you to move around, context switch, and be comfortable to be to do in other areas.

Once you feel like you've spent a good time, expand your horizons!

Think of this like an ocean with many islands. Go to one island: prompt engineering. Go narrow, get the basics right, implement some advanced stuff, and apply it to your projects. Then, jump to another island.

The nature of this field will actually put you right back to these islands because concepts are often interrelated.

This strategy allows you to keep yourself sane, still stay up to date, and gives you exposure. Along this route, you'll eventually find an island where you'll be happy staying. Then you can really go narrow and become really good :)